› › Subjective Reader Response TheorySubjective Reader Response TheoryBy on. ( )In stark contrast to and to all forms of transactional reader response theory, subjective reader-response theory does not call for the analysis of textual cues. For subjective reader-response critics, led by the work of, readers’ responses are the text, both in the sense that there is no literary text beyond the meanings created by readers’ interpretations and in the sense that the text the critic analyzes is not the literary work but the written responses of readers. Let’s look at each of these two claims more closely.To understand how there is no literary text beyond the meanings created by readers’ interpretations, we need to understand how Bleich defines the literary text. Like many other critics, he differentiates between what he calls real objects and symbolic objects. Real objects are physical objects, such as tables, chairs, cars, books, and the like. The printed pages of a literary text are real objects.

However, the experience created when someone reads those printed pages, like language itself, is a symbolic object because it occurs not in the physical world but in the conceptual world, that is, in the mind of the reader. This is why Bleich calls reading—the feelings, associations, and memories that occur as we react subjectively to the printed words on the page—symbolization: our perception and identification of our reading experience create a conceptual, or symbolic, world in our mind as we read. Therefore, when we interpret the meaning of the text, we are actually interpreting the meaning of our own symbolization: we are interpreting the meaning of the conceptual experience we created in response to the text.

He thus calls the act of interpretation resymbolization. Resymbolization occurs when our experience of the text produces in us a desire for explanation. Our evaluation of the text’s quality is also an act of resymbolization: we don’t like or dislike a text; we like or dislike our symbolization of it. Thus, the text we talk about isn’t really the text on the page: it’s the text in our mind.Because the only text is the text in the mind of the reader, this is the text analyzed by subjective reader-response critics, for whom the text is equated with the written responses of readers.

Bleich, whose primary interest is pedagogical, offers us a method for teaching students how to use their responses to learn about literature or, more accurately, to learn about literary response. For contrary to popular opinion, subjective criticism isn’t an anything-goes free-for-all.

It’s a coherent, purposeful methodology for helping our students and ourselves produce knowledge about the experience of reading. Before we look at the specific steps in that methodology, we need to understand what Bleich means by producing knowledge. Subjective criticism and what he calls the subjective classroom are based on the belief that all knowledge is subjective— the perceived can’t be separated from the perceiver— which is a belief held today by many scientists and historians as well as by many critical theorists. What is called “objective” knowledge is simply whatever a given community believes to be objectively true. For example, Western science once accepted the “objective” knowledge that the earth is flat and the sun revolves around it. Since that time, Western science has accepted several different versions of “objective” knowledge about the earth and the sun. The most recent scientific thinking suggests that what we take to be objective knowledge is actually produced by the questions we ask and the instruments we use to find the answers.

In other words, “truth” isn’t an “objective” reality waiting to be discovered; it’s constructed by communities of people to fulfill specific needs produced by specific historical, sociological, and psychological situations.Treating the classroom as a community, Bleich’s method helps students learn how communities produce knowledge and how the individual member of the community can function as a part of that process. To summarize Bleich’s procedure, students are asked to respond to a literary text by writing a response statement and then by writing an analysis of their own response statement, both of which tasks are performed as efforts to contribute to the class’s production of knowledge about reading experiences. Let’s look at each of these two steps individually.Although Bleich believes that, hypothetically, every response statement is valid within the context of some group of readers for whose purpose it is useful, he stresses that, in order to be useful to the classroom community, a response statement must be negotiable into knowledge about reading experiences. By this he means that it must contribute to the group’s production of knowledge about the experience of reading a specific literary text, not about the reader or the reality outside the reader. Response statements that are reader oriented substitute talk about oneself for talk about one’s reading experience. They are confined largely to comments about the reader’s memories, interests, personal experiences, and the like, with little or no reference to the relationship between these comments and the experience of reading the text.

Reader-oriented response statements lead to group discussions of personalities and personal problems that may be useful in a psychologist’s office but, for Bleich, do not contribute to the group’s understanding of the reading experience at hand.Analogously, response statements that are reality oriented substitute talk about issues in the world for talk about one’s reading experience. They are confined largely to the expression of one’s opinions about politics, religion, gender issues, and the like, with little or no reference to the relationship between these opinions and the experience of reading the text. Reality-oriented response statements lead to group discussions of moral or social issues, which members claim the text is about, but such response statements do not contribute to the group’s understanding of the reading experience at hand. In contrast, the response statements Bleich promotes are experience oriented. They discuss the reader’s reactions to the text, describing exactly how specific passages made the reader feel, think, or associate.

Such response statements include judgments about specific characters, events, passages, and even words in the text. The personal associations and memories of personal relationships that are woven throughout these judgments allow others to see what aspects of the text affected the reader in what ways and for what reasons.

Bleich cites one student’s description of the ways in which particular characters and events in a text reminded her of her sexuality as a young girl. Her response statement moved back and forth between her reactions to specific scenes in the text and the specific experiences they recalled in her adolescence.A group discussion produced by this student’s subjective response could go in any number of directions, some of them quite traditional. For example, the group might discuss whether or not one’s opinion of this particular text depends on feelings one has left over from one’s adolescent experiences.

Or the group might discuss whether or not the text is an expression of the author’s adolescent feelings or of the repressive sexual mores of the culture in which the author lived. Even in the case of these last two examples, for which students would have to seek biographical and historical data, the questions themselves would have been raised by a reader’s response and by the group’s reaction to that response, so there probably would be a higher degree of personal engagement than would occur ordinarily for students on whom such an assignment had been imposed. The point is that response statements are used within a context determined by the group. The group decides, based on the issues that emerge from experience oriented response statements, what questions they want answered and what topics they want to pursue.In addition, the experience-oriented response statement is analyzed by the reader in a response-analysis statement. Here the reader (1) characterizes his or her response to the text as a whole; (2) identifies the various responses prompted by different aspects of the text, which, of course, ultimately led to the student’s response to the text as a whole; and (3) determines why these responses occurred. Responses may be characterized, for example, as enjoyment, discomfort, fascination, disappointment, relief, or satisfaction, and may involve any number of emotions, such as fear, joy, and anger. A student’s response-analysis statement might reveal that certain responses resulted, for example, from identification with a particular character, from the vicarious fulfillment of a desire, from the relief of (or increase of) a guilty feeling, or the like.

The goal here is for students to understand their responses, not merely report them or make excuses for them. Thus, a response-analysis statement is a thorough, detailed explanation of the relationship among specific textual elements, specific personal responses, and the meaning the text has for the student as a result of his or her personal encounter with it.It is interesting to note that, as Bleich points out, students using the subjective approach probably focus on the same elements of the text they would select if they were writing a traditional “objective” essay. To test this hypothesis, Bleich had his students respond to a literary text, not by writing a response statement and a response-analysis statement but by writing a meaning statement and a response statement. The meaning statement explained what the student thought was the meaning of the text, without reference to the student’s personal responses.

In contrast, the response statement, just like the one discussed above, recorded how the text produced specific personal reactions and memories of personal relationships and experiences. Bleich found that students’ response statements clearly revealed the personal sources of their meaning statements, whether or not students were aware of the relationship between the two.

In other words, even when we think we’re writing traditional “objective” interpretations of literary texts, the sources of those interpretations lie in the personal responses evoked by the text. One of the virtues of the subjective approach is that it allows students to understand why they choose to focus on the elements they do and to take responsibility for their choices.In addition, by writing detailed response statements, students often learn that more was going on for them during their reading experience than they realized. Some students discover that they benefited from a reading experience that they would have considered unpleasant or worthless had they not put forth the effort to think carefully and write down their responses. Students can also learn, by comparing their response statements to those of classmates or by contrasting their current response to a text with a response they remember having at an earlier age, how diverse and variable people’s perceptions are, how various motives influence our likes and dislikes, and how adult reading preferences are shaped by childhood reading experiences.From group discussions of response statements and from their own response analysis statements, students can also learn how their own tastes and the tastes of others operate. As Bleich notes, one’s announcement that one likes or dislikes a text, character, or passage is not enough to articulate taste. Rather, students must analyze the psychological pay-offs or costs the text creates for them and describe how these factors create their likes and dislikes.

There’s a big difference between knowing what you like and understanding your taste, and it is the latter goal that is, for Bleich, the appropriate goal for the classroom. Indeed, he believes that the organized examination of taste promoted in the subjective classroom is a natural place for students to begin their study of language and literature. The focus on self-understanding is extremely motivating for most students, and Bleich’s subjective method fosters a kind of critical thinking that should prove useful to students throughout their lives because it shows that knowledge is created collaboratively, not just “handed down,” and that its creation is motivated by personal and group concerns.Source: Critical Theory Today:A User-Friendly Guide, Loistyson Second Edition, Routledge.

This article includes a, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient. Please help to this article by more precise citations. ( April 2008) Reader-response criticism is a of that focuses on (or ') and their experience of a, in contrast to other schools and theories that focus attention primarily on the author or the content and of the work.Although literary theory has long paid some attention to the reader's role in creating the meaning and experience of a literary work, modern reader-response criticism began in the 1960s and '70s, particularly in the US and Germany, in work by, and others.

Important predecessors were, who in 1929 analyzed a group of undergraduates' misreadings;, who, in Literature as Exploration (1938), argued that it is important for the teacher to avoid imposing any 'preconceived notions about the proper way to react to any work'; and in (1961).Reader-response theory recognizes the reader as an active agent who imparts 'real existence' to the work and completes its meaning through interpretation. Reader-response criticism argues that literature should be viewed as a performing art in which each reader creates their own, possibly unique, text-related performance. It stands in total opposition to the theories of and the, in which the reader's role in re-creating literary works is ignored. New Criticism had emphasized that only that which is within a text is part of the meaning of a text. No appeal to the authority or, nor to the of the reader, was allowed in the discussions of orthodox New Critics.

Contents.Types There are multiple approaches within the theoretical branch of reader-response criticism, yet all are unified in their belief that the meaning of a text is derived from the reader through the reading process. Lois Tyson endeavors to define the variations into five recognized reader-response criticism approaches whilst warning that categorizing reader-response theorists explicitly invites difficulty due to their overlapping beliefs and practices. Transactional reader-response theory, led by Louise Rosenblatt and supported by Wolfgang Iser, involves a transaction between the text's inferred meaning and the individual interpretation by the reader influenced by their personal emotions and knowledge. Affective stylistics, established by Fish, believe that a text can only come into existence as it is read; therefore, a text cannot have meaning independent of the reader. Subjective reader-response theory, associated with David Bleich, looks entirely to the reader's response for literary meaning as individual written responses to a text are then compared to other individual interpretations to find continuity of meaning.

Psychological reader-response theory, employed by Norman Holland, believes that a reader's motives heavily affect how they read, and subsequently use this reading to analyze the psychological response of the reader. Social reader-response theory is Stanley Fish's extension of his earlier work, stating that any individual interpretation of a text is created in an interpretive community of minds consisting of participants who share a specific reading and interpretation strategy. In all interpretive communities, readers are predisposed to a particular form of interpretation as a consequence of strategies used at the time of reading.An alternative way of organizing reader-response theorists is to separate them into three groups: those who focus upon the individual reader's experience ('individualists'); those who conduct experiments on a defined set of readers ('experimenters'); and those who assume a fairly uniform response by all readers ('uniformists'). One can therefore draw a distinction between reader-response theorists who see the individual reader driving the whole experience and others who think of literary experience as largely text-driven and uniform (with individual variations that can be ignored).

The former theorists, who think the reader controls, derive what is common in a literary experience from shared techniques for reading and interpreting which are, however, individually applied by different readers. The latter, who put the text in control, derive commonalities of response, obviously, from the literary work itself.

The most fundamental difference among reader-response critics is probably, then, between those who regard individual differences among readers' responses as important and those who try to get around them.Individualists In the 1960s, David Bleich's pedagogically inspired literary theory entailed that the text is the reader's interpretation of it as it exists in their mind, and that an objective reading is not possible due to the symbolization and resymbolization process. The symbolization and resymbolization process consists of how an individual's personal emotions, needs and life experiences affect how a reader engages with a text; marginally altering the meaning. Bleich supported his theory by conducting a study with his students in which they recorded their individual meaning of a text as they experienced it, then response to their own initial written response, before comparing it with other student's responses to collectively establish literary significance according to the classes 'generated' knowledge of how particular persons recreate texts. He used this knowledge to theorize about the reading process and to refocus the classroom teaching of literature.and have, like Bleich, shown that students' highly personal responses can provide the basis for critical analyses in the classroom. Has encouraged students responding to texts to write anonymously and share with their classmates writings in response to literary works about sensitive subjects like drugs, suicidal thoughts, death in the family, parental abuse and the like. A kind of bordering on therapy results.

In general, American reader-response critics have focused on individual readers' responses. American like and others publish articles applying reader-response theory to the teaching of literature.In 1961, C.

Lewis published, in which he analyzed readers' role in selecting literature. He analyzed their selections in light of their goals in reading.In 1967, published Surprised by Sin, the first study of a large literary work ( ) that focused on its readers' experience. In an appendix, 'Literature in the Reader', Fish used 'the' reader to examine responses to complex sentences sequentially, word-by-word. Since 1976, however, he has turned to real differences among real readers. He explores the reading tactics endorsed by different critical schools, by the literary professoriate, and by the, introducing the idea of ' that share particular modes of reading.In 1968, drew on psychology in to model the literary work.

Each reader introjects a fantasy 'in' the text, then modifies it by into an interpretation. In 1973, however, having recorded responses from real readers, Holland found variations too great to fit this model in which responses are mostly alike but show minor individual variations.Holland then developed a second model based on his case studies.

An individual has (in the brain) a core identity theme (behaviors then becoming understandable as a theme and variations as in music). This core gives that individual a certain style of being—and reading. Each reader uses the physical literary work plus invariable codes (such as the shapes of letters) plus variable (different 'interpretive communities', for example) plus an individual style of reading to build a response both like and unlike other readers' responses. Holland worked with others at the, Murray Schwartz, and, to develop a particular teaching format, the 'Delphi seminar,' designed to get students to 'know themselves'.Experimenters in has developed in great detail models for the expressivity of, of, and of word-sound in (including different actors' readings of a single line of ). Has experimented with the reader's state of mind during and after a literary experience. He has shown how readers put aside ordinary knowledge and values while they read, treating, for example, criminals as heroes. He has also investigated how readers accept, while reading, improbable or fantastic things ('s 'willing '), but discard them after they have finished.In Canada, usually working with, has produced a large body of work exploring or 'affective' responses to literature, drawing on such concepts from ordinary criticism as ' or '.

They have used both experiments and new developments in, and have developed a for measuring different aspects of a reader's response.There are many other experimental psychologists around the world exploring readers' responses, conducting many detailed experiments. One can research their work through their professional organizations, the, and, and through such psychological indices as PSYCINFO.Two notable researchers are Dolf Zillmann and, both working in the field of. Both have theorized and tested ideas about what produces emotions such as, in readers, the necessary factors involved, and the role the reader plays., a philosopher, has recently blended her studies on emotion with its role in literature, music, and art.

Uniformists exemplifies the German tendency to theorize the reader and so posit a uniform response. For him, a literary work is not an object in itself but an effect to be explained. But he asserts this response is controlled by the text.

For the 'real' reader, he substitutes an implied reader, who is the reader a given literary work requires. Within various polarities created by the text, this 'implied' reader makes expectations, meanings, and the unstated details of characters and settings through a 'wandering viewpoint'. In his model, the text controls. The reader's activities are confined within limits set by the literary work.Two of Iser's reading assumptions have influenced reading-response criticism of the New Testament. The first is the role of the reader, who is active, not passive, in the production of textual meaning.

The reader fills in the “gaps” or areas of “indeterminacy” of the text. Although the “text” is written by the author, its “realization” ( Konkritisation) as a “work” is fulfilled by the reader, according to Iser. Iser uses the analogy of two people gazing into the night sky to describe the role of the reader in the production of textual meaning. “Both may be looking at the same collection of stars, but one will see the image of a plough, and the other will make out a dipper. The ‘stars’ in a literary text are fixed, the lines that join them are variable.' The Iserian reader contributes to the meaning of the text, but limits are placed on this reader by the text itself.The second assumption concerns Iser’s reading strategy of anticipation of what lies ahead, frustration of those expectations, retrospection, and reconceptualization of new expectations.

Iser describes the reader’s maneuvers in the negotiation of a text in the following way: “We look forward, we look back, we decide, we change our decisions, we form expectations, we are shocked by their nonfulfillment, we question, we muse, we accept, we reject; this is the dynamic process of recreation.' Iser's approach to reading has been adopted by several New Testament critics, including Culpepper 1983, Scott 1989, Roth 1997, Darr 1992, 1998, Fowler 1991, 2008, Howell 1990, Kurz 1993, Powell 2001, and 1984, 2016.Another important German reader-response critic was, who defined literature as a process of production and ( Rezeption—the term common in Germany for 'response'). For Jauss, readers have a certain mental set, a 'horizon' of expectations ( Erwartungshorizont), from which perspective each reader, at any given time in history, reads. Reader-response criticism establishes these by reading literary works of the period in question.Both Iser and Jauss, along with the Constance School, exemplify and return reader-response criticism to a study of the text by defining readers in terms of the text. In the same way, posits a 'narratee', posits a 'superreader', and an 'informed reader.' And many text-oriented critics simply speak of 'the' reader who typifies all readers.Objections Reader-response critics hold that in order to understand a text, one must look to the processes readers use to create meaning and experience. Traditional text-oriented schools, such as, often think of reader-response criticism as an, allowing readers to interpret a text any way they want.

Text-oriented critics claim that one can understand a text while remaining immune to one's own culture, status, and so on, and hence 'objectively.' To reader-response based theorists, however, reading is always both. Some reader-response critics (uniformists) assume a bi-active model of reading: the literary work controls part of the response and the reader controls part. Others, who see that position as internally contradictory, claim that the reader controls the whole transaction (individualists). In such a reader-active model, readers and audiences use amateur or professional procedures for reading (shared by many others) as well as their personal issues and values.Another objection to reader-response criticism is that it fails to account for the text being able to expand the reader's understanding. While readers can and do put their own ideas and experiences into a work, they are at the same time gaining new understanding through the text. This is something that is generally overlooked in reader-response criticism.

Extensions Reader-response criticism relates to psychology, both for those attempting to find principles of response, and for those studying individual responses. Post- psychologists of reading and of support the idea that it is the reader who makes meaning.

Increasingly, neuroscience, and have given reader-response critics powerful and detailed models for the aesthetic process. In 2011 researchers found that during listening to emotionally intense parts of a story, readers respond with changes in, indicative of increased activation of the. Intense parts of a story were also accompanied by increased brain activity in a network of regions known to be involved in the processing of fear, including the.Because it rests on psychological principles, a reader-response approach readily generalizes to other arts: , music, or visual art , and even to history. In stressing the activity of the reader, reader-response theory may be employed to justify upsettings of traditional interpretations like or.Since reader-response critics focus on the strategies readers are taught to use, they may address the of reading and literature. Also, because reader-response criticism stresses the activity of the reader, reader-response critics may share the concerns of critics, and critics of Gender and Queer Theory and Post-Colonialism.See also.Notes and references.

Cahill M (1996). 'Reader-response criticism and the allegorizing reader'. Theological Studies.

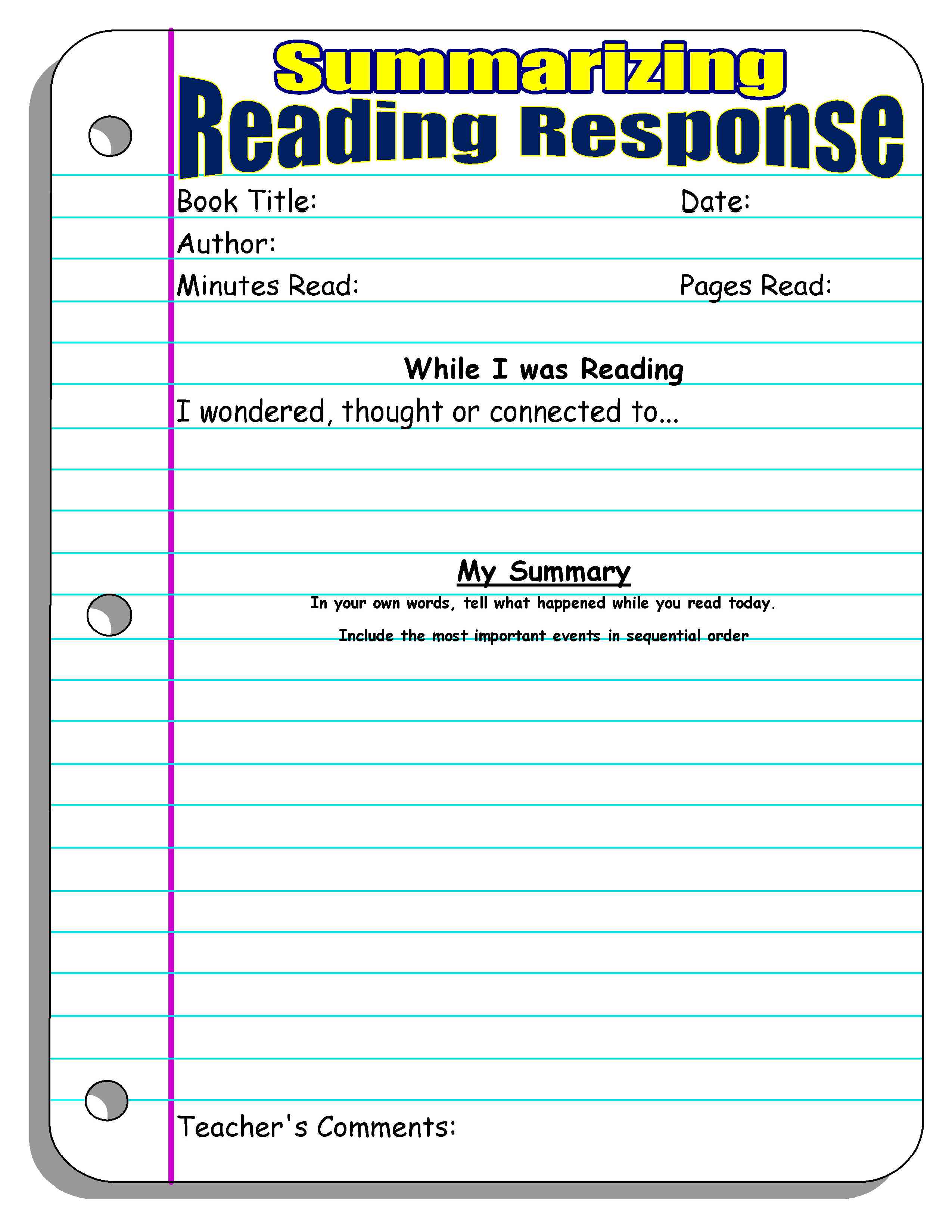

Reader Response Criticism Pdf Template

57 (1): 89–97. ^ Tyson, L (2006) Critical theory today: a user-friendly guide, 2nd edn, Routledge, New York and London. Robinson, Jenefer (2005-04-07).

Deeper than Reason: Emotion and its Role in Literature, Music, and Art. Oxford University Press., ' Religions 10, 217 (2019): 25-6. Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 282.

Ibid., 288. R. Alan Culpepper, Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel: A Study in Literary Design (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983). Bernard Brandon Scott, Hear Then the Parable: A Commentary on the Parables of Jesus (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1989). S. John Roth, The Blind, the Lame and the Poor: Character Types in Luke-Acts, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 144 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997).

John A Darr, On Character Building: The Reader and the Rhetoric of Characterization in Luke-Acts, Literary Currents in Biblical Interpretation (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992); Herod the Fox: Audience Criticism and Lukan Characterization, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 163 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998). Robert M. Fowler, Let the Reader Understand: Reader-Response Criticism and the Gospel of Mark (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1991); “Reader-Response Criticism: Figuring Mark’s Reader,” in Mark and Method: Approaches in Biblical Studies, 2nd ed., ed. Janice Capel Anderson and Stephen D.

Moore (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2008), 70-74. David B. Howell, Matthew’s Inclusive Story: A Study of the Narrative Rhetoric of the First Gospel, Journal for the Study of New Testament Supplement Series 42 (Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1990). William S.

Reader Response Criticism History

Kurz, Reading Luke-Acts: Dynamics of Biblical Narrative (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1993). Mark Allan Powell, Chasing the Eastern Star: Adventures in Biblical Reader-Response Criticism (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001)., “Reader-Response Criticism and the Synoptic Gospels,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 52 (1984): 307-24; “The Woman Who Crashed Simon’s Party: A Reader-Response Approach to Luke 7:36-50” in Characters and Characterization in Luke-Acts, Library of New Testament Studies 548, ed. Dicken and Julia A.

Reader Response Criticism Pdf Download

Snyder (London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2016), 7-22. Wallentin M, Nielsen AH, Vuust P, Dohn A, Roepstorff A, Lund TE (2011). 58 (3): 963–73.Further reading. Tompkins, Jane P. (ed.) (1980). Reader-response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-structuralism. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tyson, Lois (2006). Critical theory today: a user-friendly guide, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York and London.